The invention(s) of writing

The three little Tărtărian tablets do not fit the traditional narrative about the invention of writing, which holds that writing was first invented in Mesopotamia around 3400 BCE. This creation was seen as a unique and singular event; all other writing systems were interpreted as later, secondary inventions. New discoveries and insights have led to a revision of this monogenetic paradigm, and it is now believed that writing was created independently on at least four separate occasions (see images): in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and Mesoamerica – and some add the Rongorongo script from Easter Island as a fifth invention to this list. In the last decades, perspectives on the history of writing have also radically changed. The long popular belief that this was a straightforward evolutionary process, culminating in the invention of the alphabet, has been challenged, as it is clear that there is no hierarchy among writing systems and different scripts can co-exist for millennia.

With respect to our Tărtărian tablets, it is important to note that they are by no means a completely isolated find; numerous incised marks and signs on pottery are known from this time period and region. These signs are associated with the Turdaș–Vinča culture, a highly complex civilization which flourished in southeastern Europe from the 6th to 4th millennium BCE. Interestingly, when the signs were first discovered, it was thought that they dated to the first millennium BCE, and that they represented some form of script or notation system. Later on, however, when radiocarbon dating proved that these signs were in fact much, much older, these assumptions were drastically altered. Just as in the case of the Tărtărian tablets, they were no longer seen as possible attestations of writing.

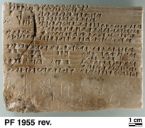

The above insights make it all the more crucial to include discoveries such as the Tărtărian tablets in discussions about early writing. Though their function may be uncertain, and we do not know whether or not the signs represent some form of writing or notation system, their very existence is nevertheless of great relevance. In case of the early Mesopotamian records, we are in the fortunate position that we also have later documents at our disposal, enabling us to follow the development of the cuneiform script. The first pictorial records can therefore be safely identified as its forerunners. In the case of the Tărtărian tablets, however, we do not have evidence of such a sequel, but that does not exclude the possibility that these tablets served a comparable purpose as the early Mesopotamian records they resemble so much.